-

23 April 2025

Category : Reportage

Fálemé: the silent river

The waters of the Fálémé River, which separates Senegal from Mali in the province of Kédougou, have a strange ochre colour. They flow slowly in a dystopically silent landscape. No children splashing in its waters, no trace of women washing clothes.

When you ask about this rare calm, there are two explanations:

–GOLD. In recent years, illegal gold mining has soared in these lands, which account for 98% of the country’s mines, and with it criminality. Gold, as so many African countries have witnessed, is not only a source of violence. It also brings public health problems and damage to the ecosystem (aquifers, crops, etc.), due to the mercury used to process it.

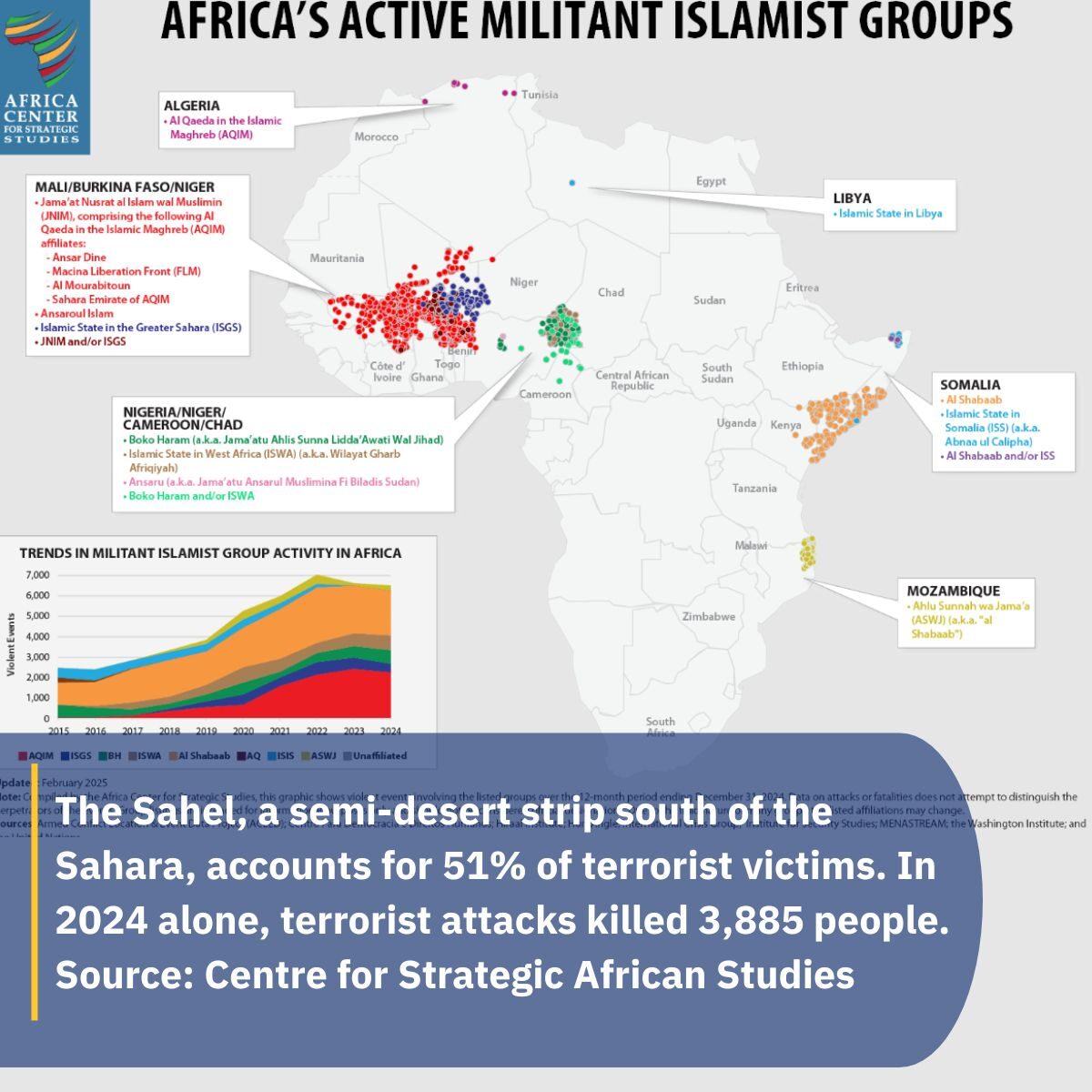

–JIHADIST TERRORISM. Mali has become the epicentre of jihadist terrorism in the last decade. The map below shows the concentration of armed groups across the river in Mali. Raids are frequent and Senegal has asked the EU for help in containing the threat.

Between the violence of the precious metal, organised crime and terrorism, some 150,000 people are trapped between the violence of the precious metal, the violence of organised crime and terrorism, and increasingly, going to the market, to school, to fetch water from the well or to a health post is a risky activity.

Sharing Spain’s experience in the fight against terrorism

The Senegalese state and its gendarmerie requested EU support in 2017 to protect the country from growing destabilisation. The Sahel, the semi-desert strip south of the Sahara that crosses Africa from west to east, is home to 51 per cent of the world’s victims of terrorism. In 2024 alone, 3885 people were killed in terrorist attacks there, according to data from the Global Terrorism Index.

Four countries agreed to collaborate with the Senegalese Gendarmerie: Spain, France, Italy and Portugal. Their security forces offered their knowledge and experience to adapt to the Sahel countries a proposal that had been successful in Spain in the fight against terrorism.

‘The GAR doctrine (Rapid Action Groups of the Guardia Civil) develops working procedures and missions based on the basic characteristics of these units: mobility, self-sufficiency, robustness and polyvalence. They are units that dispute the terrain with criminals and terrorists, limiting their freedom of manoeuvre in the most inaccessible geographical areas, where impunity is rife, regaining the initiative in the field and forcing these violent groups to protect themselves from police action and avoid the civilian population. This is how the beginning of the end of ETA began, when it ceased to be safe in the countryside and to move with total impunity,’ are the words of Colonel Miguel Ángel Hernández, who since 2024 has been directing the third phase of the European GARSI project, implemented by a European consortium and led by Spain. Hernández, who is from the Canary Islands, has previously worked in international missions with the United Nations in Guatemala and Haiti. This after more than 15 years of direct experience in the fight against ETA.

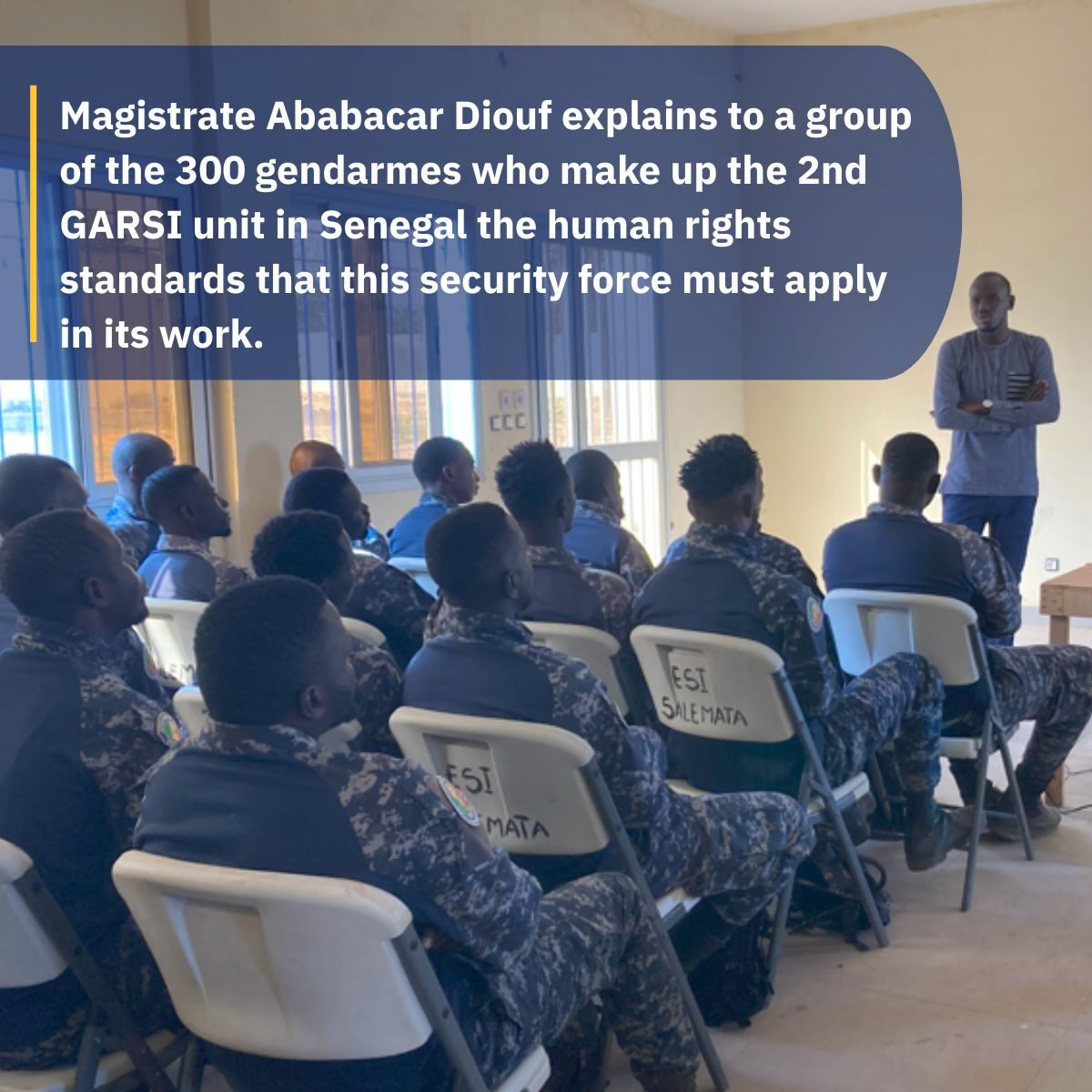

International cooperation between security forces: the security-development nexus

In February 2025, the colonel travelled to Saraya, where the country’s second GARSI unit is being formed, together with the director of the Foundation for the Internationalisation of Public Administrations (FIAP), Francisco Tierraseca. ‘I have been able to see in situ the enormous involvement of Senegal in this project. After the stabilisation of the area and the successes achieved by the first GARSI unit in Senegal, in Kidira, the gendarmerie has not even waited for the official start of the project: they have already built the basic installations for the 300 men who will make up the GARSI unit in Saraya, and the gendarmes of Kidira themselves came down here to begin the basic training of the Saraya gendarmes,’ Tierraseca said, who also stressed the importance of this border for the stability of Senegal, its own development and also security in Europe.

The mission is accompanied by Brigadier General Emmanuel Gerber and Mario Farnós, lieutenant of the Guardia Civil and institutional coordinator of the project in Senegal and Mauritania. Emmanuel has previously participated in multiple international missions, including Central African Republic, Chad, Lebanon and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In constant movement

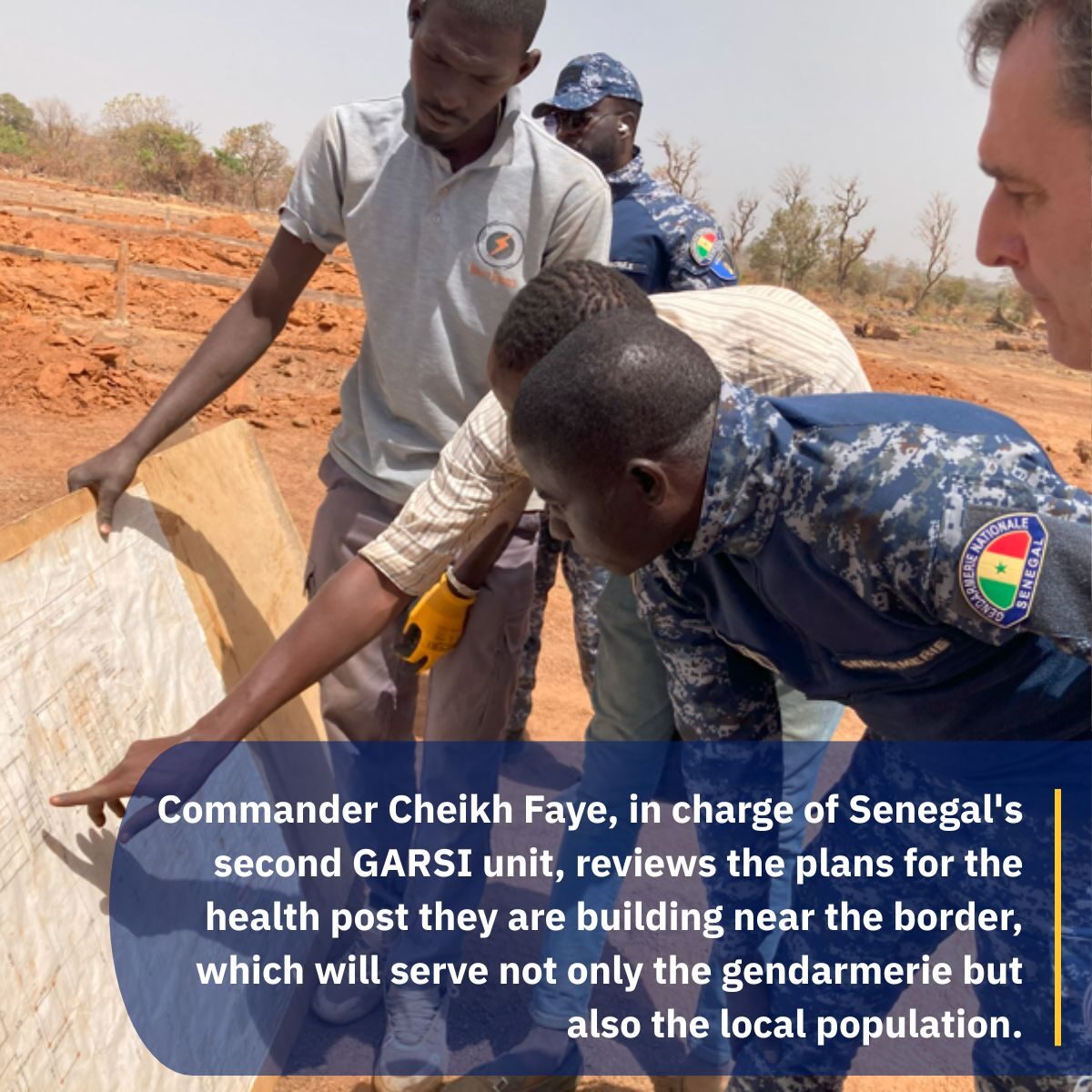

Commander Cheikh Faye of the Senegalese gendarmerie welcomes them warmly and shows them on the spot how well the work is progressing at the new Saraya barracks. He then accompanies them to one of the three mobile points deployed at the border, which can only be reached via 70 km of winding tracks shaken by dust and sand.

Mario tells us about the main characteristics of these units, what makes them different from classic gendarmeries: ‘they are units trained to work in continuous mobility, oriented towards direct contact with the population and with very specific training in areas such as physical training, explosive ordnance disposal, logistics and maintenance, judicial police, information, drone handling, explosive device detection, environmental crimes, etc.’.

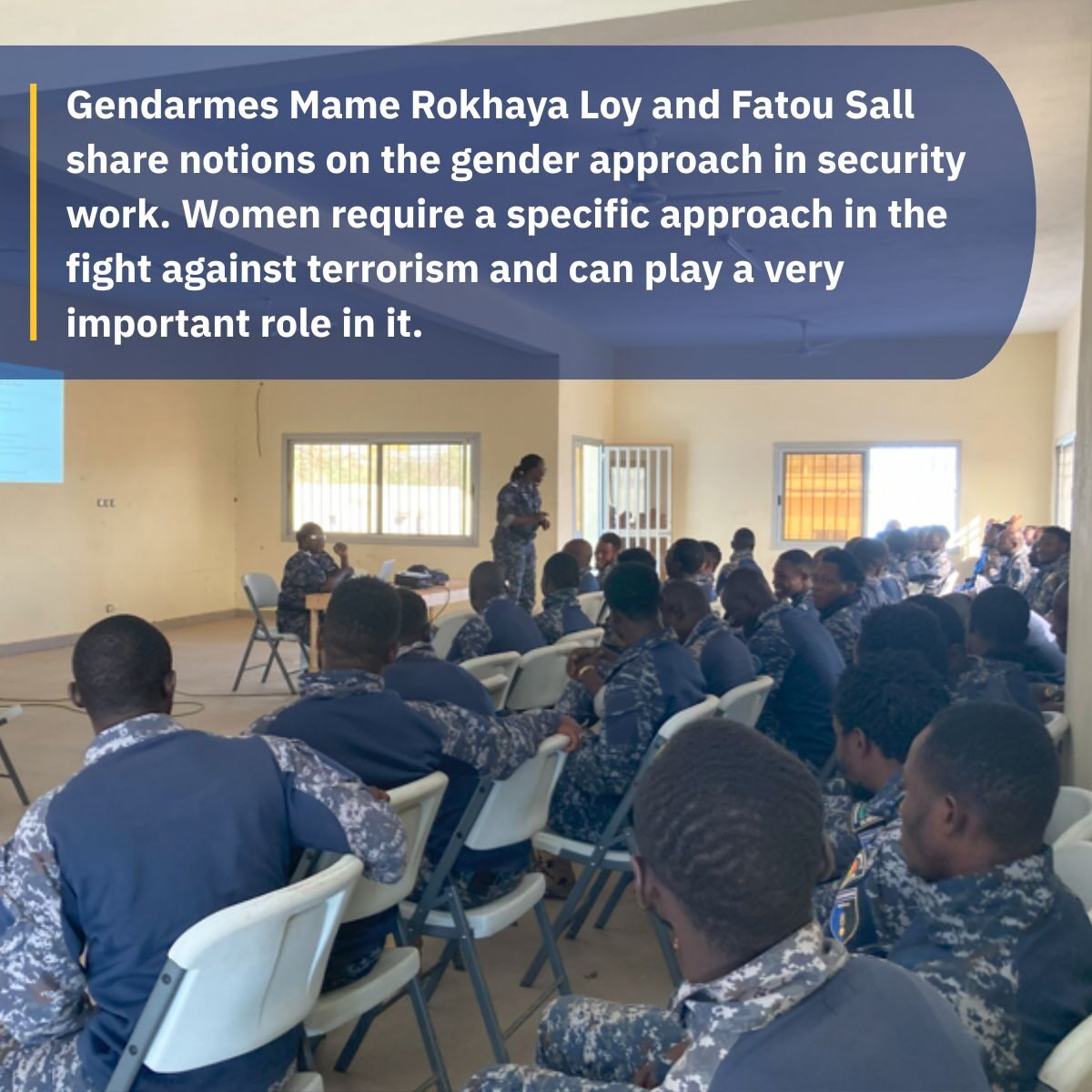

Emmanuel provides the framework for the trainings that are taking place this month: human rights and the gender approach. They are given by a person in charge of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), a Senegalese magistrate and two women commanders of the Senegalese National Gendarmerie. Beforehand,’ he explains, ’we carried out basic training, which generated a great sense of belonging and teamwork in the unit, and also the training of trainers, a key strategy for multiplying knowledge and reaching large groups of gendarmes.

Solomonic solution

The hours on the road from Dakar to Kédougou, then to Saraya, then to the border are long. In the car, we share conversations and reflections. About the need to generate security to build development, about the key moments in the fight against ETA and what it was like to be a Guardia Civil in the Basque Country, about the living conditions in these units, about the baobab trees and also about the relations between different countries that share more and more common challenges. For Tierraseca, humility and creativity in finding solutions adapted to each context are key in this form of cooperation.

Sometimes, however, with so many roads in between, consensus can only be reached through Solomonic solutions. Like the one forged by Mario and Malik, the driver: as far as Kaffrine (halfway), we drive to the rhythms of Guinea Bissau and Cameroon that Malik chooses on the radio. From Kaffrine to Dakar we return with Estopa.

Kidira, the first GARSI unit in Senegal

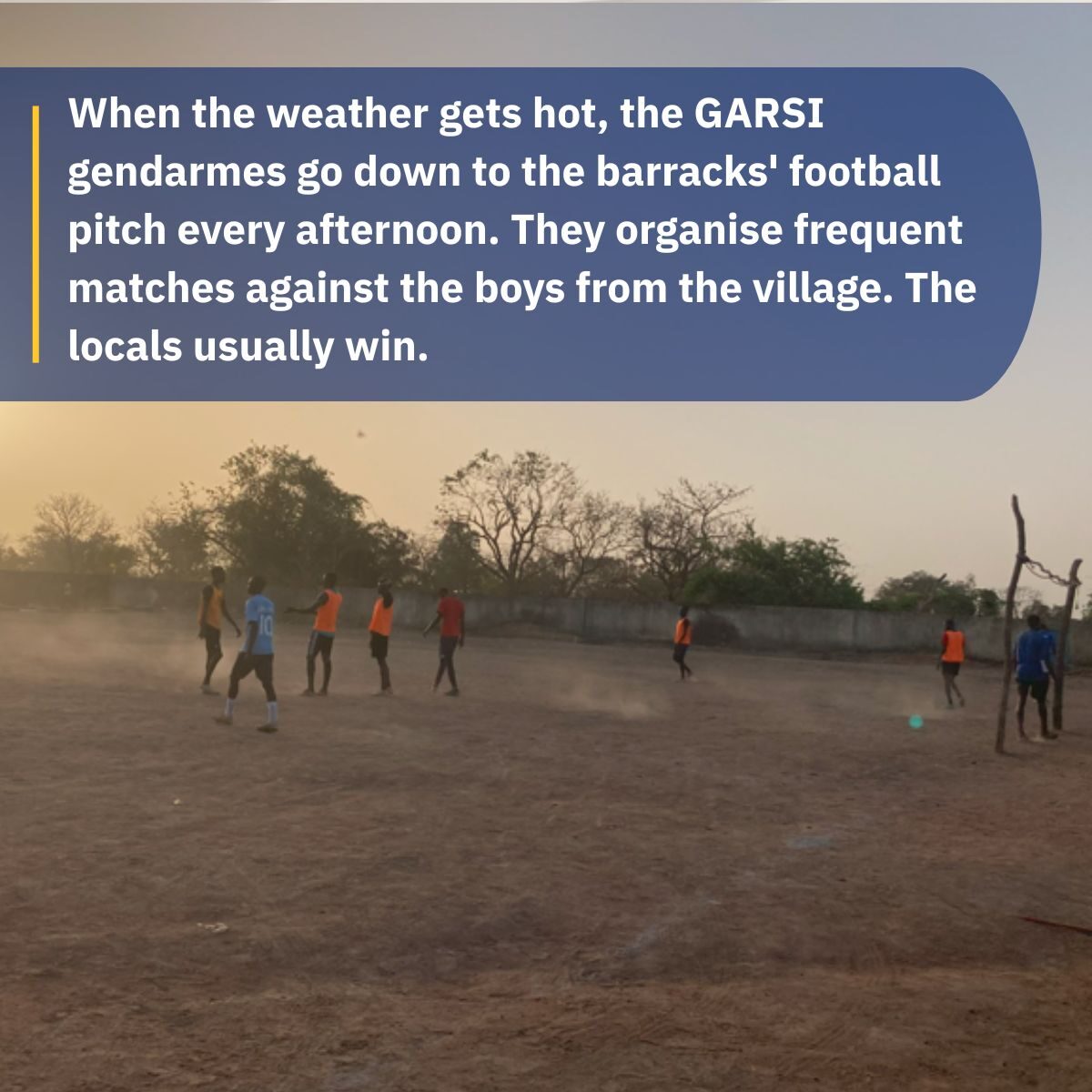

Senegal’s first GARSI unit was created in January 2019, in Kidira, with 150 gendarmes. The reactivation of the local market and the arrest of human traffickers and illegal gold miners are among the main results. Between 2019 and 2022, the unit’s infirmary provided more than 2,500 consultations for the local population.

Daouda Dembelle, representative of the youth of Sénedoubiu explains it in a nutshell: ‘the presence of GARSI has given us back the courage to move freely again’. Assah Ami Diallo, a trader in Kidira, recounted how the presence of bandits on the side of the road used to be frequent. The headmaster of the Sénoudebou school, Maky Thiam, explains how ‘children from nearby communities have returned to school because they are no longer afraid of the road’.

Their testimonies are proof of the importance of a secure base for development.

✍🏽 Alicia García, Head of Communication at FIAP

PHOTO GALLERY:

The views and opinions expressed in this blog are the sole responsibility of the person who write them.